|

|

| Home History Eng. Lit Novels Compilations and editorial work Articles Reviewers' comments Gallery Contact me | |

Peter Rowland

Biographer and Historian

www.peterrowland.org.uk

|

|

| Home History Eng. Lit Novels Compilations and editorial work Articles Reviewers' comments Gallery Contact me | |

Peter Rowland

Biographer and Historian

www.peterrowland.org.uk

Macaulay’s ‘History of England’ – chronological summary of composition

(1) From 1685 to 1702 - the truncated “authentic” text

Continuations of the saga in the 1930s by both G. M. Trevelyan and Winston Churchill proved enjoyable but not remotely in the same league. Macaulay’s five volumes remained unmatched — the tremendous opening movements, as it were, of an unfinished symphony.

(2) From 1702 to 1832 - a “compilation” volume, concluding the epic taleTantalising to Peter’s eyes, however, was the fact that Macaulay had, in effect, already written the history of the eighteenth century, for he had frequently expressed himself at length on the subject in

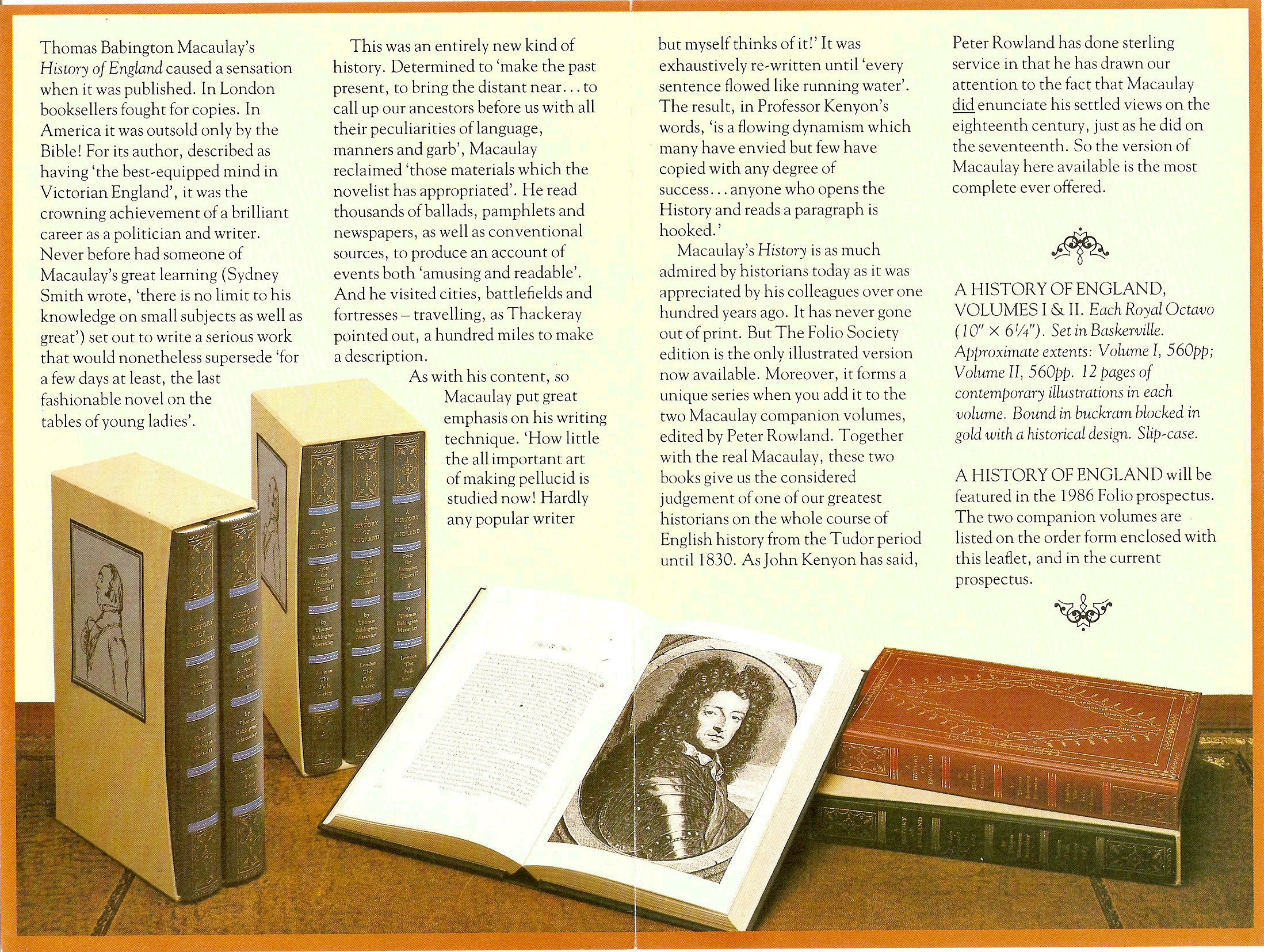

He reasoned that, by joining together in chronological sequence extracts taken from these sources, both long and short, it would be possible to compile an account, in Macaulay’s own words, of English history from the point where the original History had broken off to the passing of the 1832 Act. A fresh text, supplemented by quotations from some of the correspondence of that period, was gradually assembled and transformed into a handsome narrative. Macaulay’s History, albeit on a much smaller scale than originally planned, had finally been finished — in effect, by the man himself. The Folio Society (the only firm of publishers truly qualified to do so) happily undertook its publication in 1980 as The History of England in the Eighteenth Century. Professor J.P. Kenyon, a leading expert on the Stuarts (and also on Macaulay), provided a helpful Introduction. (More details of ‘the red volume’ will be found below.) The book attracted a considerable amount of praise and attention. Encouraged by this, the Society decided five years later to re-publish (in matching binding but a different colour) the five volumes of the original History, and Peter gladly accepted the post of Editor-in-Chief for this major project. (More details of ‘the five blue volumes’ will be found below.)

(3) From 1485 to 1685 - a “compilation” volume, prequel to the main textThe Society also invited Peter to supply a further ‘compilation’ volume which would set out Macaulay’s views on the course of English history between the accession of Henry VII in 1485, following the battle of Bosworth, and the death of King Charles II in 1685. (A couple of introductory chapters in the main History skimmed over these two centuries, but only in broad outline.) ‘These two compilations,’ said an enthusiastic John Letts, managing director of the Society, ‘will serve as “book-ends” for the authentic five volumes.’ Macaulay had indeed had much to say about the Tudors and the earlier Stuarts in his essays, and it once again proved possible to weave the various elements together to produce a lively and enjoyable volume — which, fittingly, was published in 1985. (More details of ‘the green volume’ will be found below.)

The History of England in the Eighteenth Century by Thomas Babington Macaulay, edited and supplemented by Peter Rowland, introduced by Professor J.P. Kenyon [‘the red volume’]The course of events between 1702 and 1832 is narrated in thirteen chapters — the reign of Queen Anne, the Hanoverian succession, the rise and downfall of Sir Robert Walpole, the rule of the Pelhams, European upheavals, the elder Pitt and the Seven Years’ War, King George III and Lord Bute, the Grenville and Rockingham administrations, the ageing Lord Chatham and the debut of the younger Pitt (his son), the Napoleonic wars, Britain’s victory, the tensions of the 1820s and the triumph of Reform — with a further chapter summarising literary developments. The only period about which Macaulay had very little to say was the one from 1808 to 1812, and it was here that Peter was obliged to insert a brief account of his own — incorporating within it a few fragments of the ‘genuine article’. The book concludes with the opening cadences of the original History of England being repeated, except that the tense is changed from future to past. ‘No man who is correctly informed as to the past’, runs the final sentence, ‘will be disposed to take a morose or desponding view of the future.’ 318 pages; published by the Folio Society Ltd in 1980, its red binding blocked with a design of Roger Payne circa 1785.

The History of England from the accession of James II by Thomas Babington Macaulay, Introductions by Peter Rowland [‘the five blue volumes’]This was a re-issue of Macaulay’s original five volumes, the text being taken from the edition published by Macmillan & Co. Ltd in 1913. It would be irrelevant in the present context (and gross impertinence, moreover) to summarise the contents of these five majestic volumes. The first (with its famous ‘third chapter’) concentrates on the events of 1685. The second covers the next three years and culminates in the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89. The third takes the reader from 1688 to 1690 and the fourth gets as far as December 1697. The fifth and final volume dealt, in fragmentary fashion, with the last four years of William III’s reign. Apart from writing the Introductions, Peter provided editorial notes and (where necessary) appendixes. He occasionally put into effect small corrections which Macaulay had promised to make to fresh editions of his book. In particular, Peter did a substantial amount of ‘repair work’ on the fifth volume, filling two of the gaps with material taken from Macaulay’s essays, reassigning a small portion of text to a more appropriate place in the narrative, and drawing upon a prize-winning essay about William III written by Macaulay forty years earlier to provide a more effective conclusion to the book. The first and second volumes (526 and 521 pages respectively) published by the Folio Press in 1985 and the third, fourth and fifth (582, 661 and 244 pages respectively) in 1986, their blue binding blocked with a design of Roger Payne circa 1785.

The History of England from 1485 to 1685 by Thomas Babington Macaulay, compiled, edited and introduced by Peter Rowland [‘the green volume’]A narrative of the course of events between 1485 and 1685 in ten chapters — the reigns of the five Tudor monarchs and those of James I and Charles I, followed by the Civil War, Cromwell and the Interregnum, and climaxing with the restoration and reign of King Charles II. — plus four chapters dealing with Shakespeare, Bacon, Milton and Bunyan. Peter cautions the reader, in his Introduction, to be on guard against the manner in which the historian chooses to present his story, level his accusations and manipulate his evidence. ‘He must allow for the fact that Macaulay finds it almost impossible to stand on the sidelines but is compelled to hurl himself passionately into the fray, dealing out commendations here and condemnations there. He believed, quite simply, that he had to shout very loudly in order make himself heard and that it ill-behoved a narrator to admit to uncertainty on any issue. He speaks throughout, therefore, with the voice of authority. He has no doubts about anything. The purists may complain (and, indeed, have done so, both then and now) that this is not a proper way to write history ... [but] Macaulay was swept along, more often than not, by a wave of honest indignation. He really did feel called upon to exercise his talents in a semi-judicial fashion, sometimes as advocate and sometimes as prosecutor. Only by sitting in judgment on the past could he bring home to his readers the pitfalls which they needed to avoid in the future. It is not, however, for the quality of his judgments that we turn to Macaulay — although many of them, it must be conceded, stand up surprisingly well — but for entertainment and excitement. The one thing emphatically not in doubt is the sheer force of his narrative power, magical, dynamic and inspired. He stands virtually unrivalled as a teller of tales. That is why we still read him today while the works of many fellow-historians, rather more deeply researched, extremely cautious and tentative in their conclusions and infinitely more tedious, gather dust on the shelves. It is why he will still be read for the next two hundred and three hundred years and, indeed, for as long as the English language, and its literature, endures.’ 337 pages; published in the UK by the Folio Society Ltd in 1985, its green binding blocked with a design of Roger Payne circa 1785.

|